A Crossroads for Shared Governance

I used to like to point out that all top public universities have faculty or university senates. As of September 1, I can no longer make that claim.

Over the summer, Texas passed SB 37, which dramatically shifts oversight over curriculum and hiring away from faculty and into the hands of governor-appointed university regents. The law also creates an office to monitor compliance with new restrictions and the ban on DEI initiatives, imposing severe financial penalties on institutions that fail to keep faculty "properly in their place." Ahead of the compliance deadline, the flagship UT system dissolved faculty senates and replaced them with administrative "faculty advisory groups" with no final decision-making authority. UT Austin's website now reads: "Per SB 37, the Faculty Council is dissolved as of September 1, 2025."

Few people appreciate how crucial these shared governance bodies have been to the remarkable success of American higher education over the past 80 years. There is a clear correlation between how early shared governance became part of a university and its current overall status. Eight of the ten top public universities had some form of shared governance dating back to before World War II—with only North Carolina and Georgia Tech as exceptions. And now, Texas.

The University of Texas at Austin currently ranks 7th among public universities in US News & World Report. The UT system has produced eight Nobel Prize winners and stands as a jewel in the crown of American public higher education. Like all research universities, UT's success and stature are inseparable from higher education's shift away from concentrated power toward the unique system of shared oversight that emerged nationwide between the 1920s and 1950s. The UT Faculty Council dated back to 1928—just 13 years after the founding of the AAUP, when shared governance was still exceptional in higher education. Today, after almost a century, this senate has been erased by legislative fiat.

Had the legislature understood how closely the seemingly unglamorous work of shared governance was tied to their flagship institution's historic success, perhaps they would have hesitated. But probably not. It's no longer clear whether world-renowned universities with international research agendas are what they want.

Much attention in recent months has rightly focused on the devastating impact of lost grants and federal support. Very little attention, however, has been directed toward the dismantling of shared governance and faculty oversight of curriculum. In the long run, I fear the erosion of shared governance will prove every bit as catastrophic as funding losses—and likely more long-lasting. While federal investment in higher education will take many years to restore, many grants will eventually return. But the odds of Texas faculty recovering oversight of curriculum and faculty hiring are vanishingly slim. With faculty oversight stripped in favor of political appointees' non-expert judgment, higher education could rapidly return to what it was before the birth of the modern research university.

The Rise of Modern American Higher Education

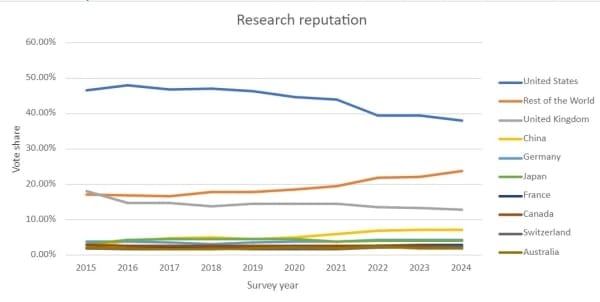

I began graduate studies in the late 1980s and, like all my colleagues, inherited certain assumptions about our profession—among them the international reputation of U.S. higher education institutions. While there have been signs of downward pressure recently, according to Times Higher Education polling, the overall international reputation of our universities continues to eclipse all rivals as of 2024. A 2024 report logged a record number of international students in U.S. institutions: over 1.1 million.

Less than a century earlier, in 1930, fewer than 10,000 international students attended American universities, up from roughly 300 in 1905. Before 1880, no one would have considered an American university worth the cost of travel to attend.

Before the research university, training doctors and lawyers was haphazard at best. In many parts of the country, it required little more than looking up how to spell "physician" or "attorney" and hanging a shingle. Presidents and boards wielded absolute power, often fighting among themselves over control but never considering that faculty or students might have a voice in university operations. Hiring was controlled largely through patronage, local reputation, and denominational affiliation. There was little credentialing—not one founding faculty member at Ohio State in the 1870s held a PhD—and no concept of peer-reviewed scholarship. Faculty were terribly underpaid with no job security, and with no national marketplace for scholars, job mobility was nearly impossible.

Student life was little better. When admission wasn't based on connections or ability to pay full tuition upfront, it hinged on "classical" standards: recitation of memorized Latin and Greek, arithmetic, and some geography. Many students came through their college's own "prep department," making these institutions effectively an extension of high school. Science labs were rare, curriculum was almost entirely standardized, and electives didn't exist at most schools.

No one understood the obstacles facing mid-19th-century American higher education better than Henry Philip Tappan. "In our country we have no Universities," he wrote in his fascinating book University Education in 1851, shortly before becoming president of the University of Michigan:

Whatever may be the names by which we choose to call our institutions of learning, still they are not Universities. They have neither the libraries and material of learning, generally, nor the number of professors and courses of lectures, nor the large and free organization which go to make up Universities.

At Ann Arbor, Tappan sought to build the nation's first research university—one that was secular, rigorous, and dedicated to serving students and the communities to which they would return. He lasted little more than ten years before the Board removed him. His commitment to merit-based faculty hiring and his refusal to court churches and their favored faculty alienated many regents. The Democratic partisan press also targeted him for supposed elitism. Upon his removal, he moved his family to Europe, where the modern research university didn't need to be carved out of frozen, resistant western soil.

While international scholars didn't come to American universities in the 19th century, over 10,000 American scholars traveled to Germany for advanced degrees at research universities like Berlin, Göttingen, and Heidelberg. Upon their return, these scholars became the academic and administrative leaders of leading universities nationwide, importing a transformed version of the German model. When the first American research university following this model was founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins' founding president Gilman recruited a roster of accomplished scholars—many with advanced degrees from Göttingen or other German institutions.[^This includes the economist Richard T. Ely (Heidelberg), the classicist Basil Gildersleeve (Göttingen), the historian Herbert Baxter Adams (Heidelberg), and the chemist Ira Remsen (Göttingen)]

The Birth of Faculty Governance

The emergence of professional scholarly societies in the 1890s elevated faculty influence both within and outside their universities. While we commonly associate the AAUP's 1915 founding with its pioneering defense of academic freedom (adapted from the Humboldtian model of higher education), it began primarily as a confederation of professional societies, bringing them together to advocate for greater respect, compensation, job security, and a voice in university affairs.

While some founding AAUP members favored faculty unionization as one approach to gaining improved professional rights, the organization's platform before 1970 opposed faculty unions. This made sense then and arguably still does today, though a complete collapse of shared governance will certainly expand the case for faculty unions. After all, the faculty career before the late 19th century was oppressive: poor pay, poor working conditions, and no voice in the university's core teaching and research mission. Professional organizations and the AAUP worked to move faculty into something like middle management—pushing for increased classroom and research autonomy (academic freedom), job security (tenure and transparent promotion policies), and oversight responsibilities in curricular and hiring matters. This was hard to square with early 20th-century labor movement aspirations.

Professional organizations alone wouldn't have elevated faculty power without new pressures on Boards and Presidents that made redistributing oversight responsibilities increasingly appealing. Universities were growing rapidly in size and complexity in the early 20th century. At Ohio State, for example, in 1900 the university was divided into six colleges, with the College of Arts, Philosophy, and Science having 55 faculty and lecturers serving 447 undergraduate and graduate students. By 1940, on the eve of the founding of the university's first shared governance body, Arts and Sciences faculty numbered in the hundreds. Bachelor of Arts degrees had grown from five awarded in 1900 to 323 in 1940, while the Bachelor of Chemistry degree—nonexistent in 1900—reached 329 in 1940.

As American universities grew in size and complexity, managing these institutions exceeded the capacity of boards and central administration. Faculty demands for increased oversight of curriculum and teaching-related decisions had been growing, and other universities had been adopting faculty or university senates since the mid-1920s, proving the arrangement's effectiveness. The specter of faculty unions also loomed as more professions unionized, including inside higher education institutions.[^For example, dining workers at Harvard organized in the 1930s as Local 186.]

Another pressure was driving leadership toward acceptance of greater faculty engagement in shared governance, especially before and after World War II. As higher education institutions expanded and universities grew, demand for qualified faculty became intense when PhDs were far from ubiquitous. Elite eastern institutions drove up wages trying to maintain their status in an increasingly competitive market, and a national marketplace for talented young PhDs emerged through professional societies. This competition resulted in the ubiquity of the PhD by the 1950s and 1960s and a competitive research arena centered on peer-reviewed journals and academic conferences. This gradually increased both faculty wages and status at major universities, strengthening their negotiating positions individually and collectively.

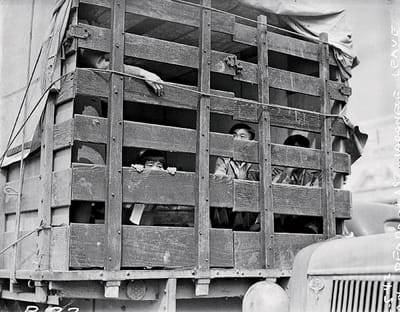

The increased complexity of university management, combined with fears of labor unions and growing competition for faculty, led more university Boards to accept and even welcome shared responsibility and oversight, especially in curricular matters. Those who resisted before the War quickly joined the trend afterward. If universities were growing before 1940, they would explode afterward as the baby boom and GI Bill brought waves of new students. From 1940 to 1950, with veterans making up half the student population, overall numbers jumped 64% from 1.4 to 2.4 million. When the baby boom wave hit in the 1960s, students in American higher education more than doubled from roughly 3.6 million to 8.6 million between 1960 and 1970, hitting over 10 million in 1975.

Further contributing to university size and complexity was the expansion and diversification of the research mission. During the War, higher education and the federal government discovered mutual benefit in closer cooperation, resulting in a deepening interdependence (currently being weaponized against higher education by the current administration). Along with the baby boom and GI Bill, which dramatically increased college demand and access, this new financial partnership sparked rapid growth in research universities and the need for more faculty to oversee labs, manage research staff, and handle the complex work of federal and international research proposals and compliance.

It's no surprise that by the time I entered the profession, faculty oversight of curriculum, hiring, and research felt natural—as if it had always been that way. How could the modern university, still growing in the 1980s and 1990s, function without faculty on the bridge? Until quite recently, it seemed unimaginable that this would change. That is no longer the case.

It's hard to overstate how much the research university's historic success required and was empowered by this redistribution of managerial responsibilities. The transfer was never true co-management—Presidents and Boards have always retained the power to overrule faculty on issues under faculty oversight. That Presidents and Boards have used this power sparingly testifies both to this model's effectiveness and to the reputational risks institutions face when stripping faculty experts of their role in overseeing curriculum, research, and hiring.

While faculty like to talk of their "control" over curriculum, that has always overstated the case, creating misperceptions both internally and externally over time. The acceptance of faculty management principles has always been an uneasy compact, one that must be reaffirmed through shared governance institutions at college and departmental levels and through faculty and university senates. It could always end tomorrow. In several places around the country, it's already over.

Should the death of shared governance spread beyond states already severely impacted, the results will be disastrous—and not only for faculty. University reputations nationally and internationally will suffer, leading to declining quality of students and faculty. For public institutions, it will damage state economies as universities founder on bad decisions made by politicians and ideologues, accelerating the exodus of talented young people on whom the state's future depends. It will weaken degree value for alumni and accelerate the movement of a younger generation away from higher education entirely. It won't be long before U.S. higher education returns to where it came from.

The Work of Shared Governance

The legislative attack on faculty senates in Texas should be creating shockwaves across higher education, raising significant alarm not just among faculty but trustees and alumni. That it isn't signals how little understanding exists about university senates' work and importance. These bodies tend to appear in news only when passing controversial resolutions. But for functioning shared governance, the real work happens in decidedly unglamorous rooms where committees engage in collaborative oversight of everything from curriculum to university rules to student codes of conduct.

Senate is where faculty (and in university senates, students and staff as well) demonstrate daily the benefits of collaborating and communicating outside the administrative bubble. It's the daily reaffirmation of the uneasy compact painfully reached in the early 20th century, in which faculty would handle day-to-day curriculum and research management. In exchange, trustees have seen their institutions and higher education as a whole transform from parochial ponds to a global engine of discovery and transformation.

Sadly, many university community members don't grasp either the legacy or ongoing daily work of their senates, as became painfully clear in March 2024 when the University of Kentucky's President and Board dissolved the senate and replaced it with an advisory body. The move stripped faculty of decision-making power in curricular and other matters, shifting power back to the President and Board, where it had wholly resided when American universities were provincial backwaters. In the time it took to count Board votes (19-1), they wiped out a senate that had existed since 1918, re-centralizing authority with the President and Board.

When this happened, I was finishing my ninth year as a senator and had recently put my name forward for the position of senate secretary. I know UK well—my son's godfathers live there, one a professor in the English department. I wrote to ask how faculty were taking the news but found him largely indifferent. It wasn't clear, he said, what the university senate ever accomplished or how its disappearance would affect faculty lives.

This was no doubt the majority position among faculty, and I understand it. Since the modern research university's successes were secured decades ago, faculty have been raised to think of themselves as semi-autonomous free agents. In many fields, research faculty don't simply contribute to institutional reputation but also to its bottom line, bringing in federal grants, securing patents, and supporting various operations and positions. Teaching remains at our core, but as the research enterprise grew—especially as state funding decreased—investment in and dependence on research grants and intellectual property grew steadily. Faculty are increasingly incentivized to see themselves as research leaders and entrepreneurs—as free agents who could take their talents to the highest bidder, but also as contracted talent who could be cut loose if they fail to deliver the funding dollars for which they were hired. These aren't conditions to breed the civitas necessary to manage shared governance foundational to the modern research university, just as such civitas would not set individual faculty up to be the research leaders universities depend on and reward.

The problem, sadly, is that faculty have come to imagine the protections and autonomy of the professoriate as inevitable. with administration and university bureaucracy as interference at best. What can the bureaucratic work of shared governance possibly contribute to faculty incentivized to think about their institutions as something akin to management of a sport team that has negotiated for their talents? That shared governance bodies played a key role in securing the modern professoriate's foundational arrangements—and daily maintain those agreements—becomes harder to imagine with each year.

Until, of course, they're gone. Texas eliminated shared governance on September 1. Little more than a week later, a faculty member was fired by the university president after a video circulated showing a student confronting the instructor for teaching that there are more than two genders and the instructor insisting on her right to teach her expertise area as she saw fit. In addition to the faculty termination, the English Department chair and the Arts & Sciences Dean were removed. All this occurred without due process, in obedience to Internet mob demands. It took days for the cost of losing shared governance to become horribly clear. Yet still, the dots aren't being connected.

When colleagues ask after the reasons for my dedication to this work, I'm often caught between conflicting impulses. If I speak in broad, grand terms about why this matters, it sounds so abstract or grandiose as to be obnoxious—as indeed I risk doing here. If I detail the daily work's minutia, which is where grand principles are reaffirmed through committee work, I'll sound like a bore (or frighten them off, worried that whatever I have might be contagious).

And then there is the unexpected gift of this work that I find hardest to share. Contrary to all I'd been raised to believe since I was a student, I have discovered that every corner of the institution is populated by remarkably decent and very dedicated people, all of whom strive to keep this vast machinery running. To be sure, I've met individuals whose decisions I disagree with. But I've yet to encounter anyone not working on behalf of what they believe are in the best interests of the university and the communities we serve.

At a school this size, no individual—even the President—can grasp all the structures and systems. This makes it easy for faculty, staff, and administrators to retreat into local allegiances and perspectives. But if the current moment has taught us anything, it's that our careers and fields don't exist without each other and the university which we conspire to bring into being with every class, budget, hire, meeting, construction project, and communication. Whether employed at Harvard or a red-state public like my own, it could all fall apart in a moment.

The specialized distribution of oversight is necessary for the operation of a large complex 21st-century university. Faculty have demonstrated over the course of decades their effectiveness at managing curriculum, research, and the hiring and promotion of faculty. It should be no surprise that faculty would imagine that this expertise is the most important aspect of their institution and therefore that they are the unacknowledged true legislators of the university. The success of specialized oversight inevitably risks bubbles whereby those specialists imagine their domain and expertise to be the most, if not only, meaningful work at the institution. But of course the research mission does not exist without a vast operation ensuring that the research faculty conduct is always aligned with law and the requirements of granting agencies. Similarly, the hiring of faculty is not possible without the human resources and fiscal offices who can ensure that hiring process will be conducted ethically and legally and that we are able to support the new personnel through a long career.

I could go on, pointing to all the work taking place at a modern university—so often disparaged as "bloat" by faculty who see these offices as obstacles to their research and teaching and rarely as the legal, financial, and political work that enables teaching and research to continue. Faculty can accept the valuable role of student affairs, because it has taken over from them their historic role of monitoring student conduct and serving in loco parentis. Beyond that, they are not sure what most of the administrative offices do.

On one level, this is how it should be. Specialization means not having to know how it all works so one can focus on what you do best with minimal distractions. But when specialization gives way to the assumption that only your work matters, the center quite literally cannot hold. Faculty rightly point out that teaching and research are the reason for the university's existence. But the survival of those missions has never depended solely on the work and expertise of faculty. Without offices of government affairs, communications, fiscal, risk management, compliance and policy, human resources, legal affairs, development, and facilities and operations (to name just a few) none of this continues, including teaching and research.

If the pods of specialization and distributed management is what allows the modern university to operate, it is shared governance that perforates the bubbles sufficient to bring in limited but focused cross-pollination. Senators sit on committees with staff and administrators from dozens of offices and help them not lose sight of the faculty and students who lie at the foundation of the research university. In turn, we learn from these staff and administrators about the specialized work they do on behalf of the university. And through that ongoing process of mutual understanding and engagement, we open up limited but vital pathways for collaboration, input, and communication to perforate the walls that usually divide us into discrete roles and responsibilities.

The Fate of Shared Governance in an Age of Concentrating Power

Shared governance is foundational to the modern research university accomplishments and societal benefits. But as the barriers of specialization have grown more impenetrable, it has failed to make its own case.

I realize now that it was a mistake to imagine the value of the work would speak for itself—or that the governance system I inherited was sufficiently strong and cherished to weather the 21st century. Looking through the archives, I see this work fading further into the background over recent decades. Once it was featured regularly in the university paper, with agendas posted monthly. Today it appears only during moments of protest or controversial resolutions—moments that are the bug, not the feature, of shared governance, most in evidence when the system isn't working as it should. If this is all one knows about senate, it's hard to imagine being inclined to defend it.

In administrators' and trustees' eyes, it risks becoming little more than a printing press for impossible demands and bad publicity. In many faculty members' eyes, its ability to "speak back to power" is so limited by its integration into university governance structures as to make it seem the weakest of tea. Perhaps, many on both "sides" think, we'd be better off without it.

Yet the fact that senates are being neutered or dismantled at an accelerating pace clearly reminds us that some powerful people understand that university senates are doing something that they need to stop.

In April 2025, the Indiana state legislature folded provisions into its biennial budget (HEA 1001) that formally stripped faculty senates of decision-making power. The law adds a new Indiana Code chapter making any faculty governance organization's actions advisory rather than binding. At a time when higher education faces unprecedented attack, faculty governance at Indiana's public universities—including Indiana University and Purdue—was reduced to an advisory role, with additional constraints on academic programs and boards.

One final example, close to home: HB 96, signed June 30, 2025, requires Ohio public university trustees to control the curricular gates, with senates legally reduced to an advisory role. HB 96 adds R.C. 3345.457, requiring every public university board of trustees to adopt a curricular approval process for "programs, curricula, courses, general education requirements, and degree programs." The statute explicitly bars trustees from delegating this authority to senates or other bodies.

Many colleagues see this impact as largely symbolic. After all, Trustees have always had final authority; this just makes that veto power more explicit. The Board has consistently endorsed senate curricular decisions, and I believe this current Board—or a future one similarly constituted with individuals taking the university's reputational and fiscal health as their highest responsibility—will, within the bounds of the new law, continue to work with shared governance. But Boards change, and following SB 1's signing into law in March, they'll transform more quickly, with shortened terms for governor-appointed positions.

But even short-term, it will make a difference. The new statutory language requires that no curricular decision—including our 1,500 annual course proposals—can be made independent of Trustee approval. More ominously, it means anyone whose program proposal is rejected at any stage in our processes—whether by a department or by senate committee—need not accept this peer review as the final word on the matter.

HB 96 doesn't abolish faculty senates in Ohio, but it takes a troubling step in that direction, codifying senate's role as advisory in curricular matters while centralizing curricular authority with Boards. Combined with SB 1's new statewide mandates, it narrows campus-level autonomy in areas long under faculty oversight and managed by shared governance. It returns to the Board, unasked, burdens they had willingly distributed decades ago.

All of this makes shared governance work more vital than ever as we seek to preserve—for the good of our university and its students, staff, alumni, and taxpayers and other stakeholders—the collaborations and distributed oversight foundational to the modern research university. But it also makes it more challenging, especially when we realize we must explain what we do and why it matters when there are days we all have trouble even explaining it to ourselves.

This is volunteer work. My senators and committee members take time from their workdays or studies to engage in meetings with constituent groups, with the university senate as a body, and with committees on which they sit. But the people who give of themselves this way are rarely temperamentally inclined to self-promotion. Yet, if we fail to amplify this work—to make it legible to administrators, legislators, trustees, and the students, staff, and faculty who make up our many communities—far more than shared governance's future is at stake.

It's too late for Texas and Kentucky. The rest of us are fast running out of time.

Subscribe (always free)

Subscribe (free!) to receive the latest updates

Member discussion