Digital Hygiene & the Ivory Scare

Part 2: Everything Else

For many of us working in higher education, email commands more hours in our working day than in-person meetings and class time combined. As discussed in the last post, email is especially exposed to public records requests and vulnerable to a wide range of attacks that will only get more sophisticated and targeted in the age of AI and—there is good reason to fear—increasingly motivated surveillance regimes.

As one example of the latter, the New Republic shared a story today of a 67-year-old who wrote a Gmail message to Homeland Security asking them not to deport an Afghan refugee. Within a few hours he received notice from google of an administrative subpoena for his information, and within a few days he was visited by DHS agents at his house.

In this post I want to talk about digital hygiene when it comes to the "everything else" of our digital lives. The same small print applies as last time: I am not a cybersecurity expert, and all I have to offer here is an account of where I myself am in this ongoing journey to balance safety with sanity. I have much to learn, and the technologies and political landscape are changing so fast as to make even the things I get right at best a snapshot in time. Some of what I say here will sound paranoid to many; others may find my approach to privacy and digital hygiene far too lax. Your own strategies will depend on many factors, including your risk tolerance, your employment status at your institution, and what kinds of work and communication you engage in online.

📖 Contents

This post is long. I thought about breaking it up into 2 or 3, but I am ready to move on from this topic and get back to a range of other things that drew me to create this newsletter in the first place. So I drop it all here, with an index of sorts so folks can read what interests them and ignore the rest. After all, if you don't have any social media accounts or ever use AI, you don't need to read my hand-waving warnings about the dragons that reside in those spaces (especially social media).

But there are a few things besides email that all of us do use, including web browsers and web search. To frame my discussion of those seemingly innocuous activities—and by way of connecting the previous post to this one—I will begin with a jeremiad—no doubt preliminary to more extensive ones to come—about the platformization of the Internet and why this is no longer the Internet 1.0—or even 2.0—with which many of us came of digital age.

Google, Amazon, & the Enclosure of Everything

Oh, Google. I can't quit you. Like the Hotel (Mountainview) California, you can check out any time you like, but you will never leave. The digital enclosures of the platform economy create the illusion that all is arranged to meet our every need and that we are free to come and go as we please. But as the last twenty years have shown, there increasingly is no outside to the platform economy. To leave one platform's enclosures—whether Google, Microsoft, Amazon, or Apple—is to find yourself within the enclosure of another "digital fiefdom," to borrow from Yanis Varoufakis, the economist and former Greek finance minister, who brilliantly reveals the story of the invisible enclosures in which we now find ourselves in Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism.

It was not always this way. Back in 1998, when Google emerged as a search engine, it had no monetization plan. It wasn't even clear that the Internet was something that could be monetized at the time. Most of what constituted the Internet in the mid-90s era of Web 1.0 was freely offered and freely contributed to. It was, however briefly, something akin to a digital commons, relying on volunteer labor and built on a publicly supported (government and higher education) infrastructure.

The Internet Movie Database was for this film nerd the project that made me believe for a time that the Internet of the 90s could be something truly different. It began as one person's passion project before moving to the usenet group rec.arts.movies and building up its database through collaborative effort of the participants. When the world wide web came online in 1993, IMDb.com was among the first 200 websites, at the time housed at the University of Wales. I followed it from usenet to the web as an occasional contributor and frequent user. And then, in 1998, Amazon acquired it, one of the young company's first acquisitions in what would become one of the largest fiefdoms of the 21st century. All the volunteer labor of participants on usenet and the university-hosted website was bundled up and sold off, uncompensated, to serve as a small brick in a vast empire of monetizable data.

The same year Amazon acquired IMDb, Google began its existence as a humble search engine. The web was expanding at breakneck pace in the 5 years since IMDb joined the new world wide web. Google was far and away the best search engine at the time, due to its ability to map relationships between websites, allowing search results to reliably place more relevant results higher in the output. It was a revelation at the time, and its effectiveness allowed the early Internet to scale exponentially—from roughly 130 websites in 1993 to over 2 million in 1998.

While the company's limited revenue initially came from licensing its powerful search engine to commercial websites, it was not long before its value to companies looking to advertise their way to visibility in a chaotic new marketplace led to the development of what would be (and still remains) Google's primary business: advertising. In retrospect, the moment its search results were being tweaked in favor of advertisers, the writing was on the wall. Heck, even the company's founders, Larry Page and Sergei Brin, had warned against the dangers of combining search and advertising in their 1998 paper, "The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine": "We believe the issue of advertising causes enough mixed incentives that it is crucial to have a competitive search engine that is transparent and in the academic realm," the Stanford PhD candidates wrote. Within a couple of years, no longer in the "academic realm," they built precisely what they had warned against. They were profitable shortly thereafter.

Today of course, Google/Alphabet owns Gmail, Google Docs, Google Photos, Google Maps, Android, YouTube, Waze, Nest, Fitbit, DoubleClick, Gemini, NotebookLM, and much more. This year, Google will be diving into the terrifying new fashion-meets-surveillance market with the release of their Smart Glasses. All of these projects and holdings exploit the synergy between customer data collection on one hand (driving habits, search history, smart home apps, exercise, video uploads and views, your photos, documents, and of course your emails) and the monetizing of that data on the other through, for example, their DoubleClick ad business. And of course now their AI models slurry up the Internet Google has been indexing for decades alongside all the search, driving, smart home/IoT, and other data they have been harvesting for years.

If this sounds like a Black Mirror episode, that is only because Black Mirror was always closer to social realism than speculative fiction. Earlier this year Google invited users to opt in to "Gemini with personalization," which grants the AI model access to your search history "to provide responses that are uniquely insightful and directly address your needs." The amount of data across Google's products to which you are now encouraged to grant Gemini access has grown considerably, as Google CEO Sundar Pichai announced at Google I/O in May. But any loss of privacy, we are assured, will be worth it for the convenience. Here is how Pichai describes the new gmail feature of "personalized smart replies."

Let's say my friend wrote to me looking for advice. He's taking a road trip to Utah and he remembers, I did this trip before. Now, if I'm being honest, I would probably reply something short and unhelpful. .... But with personalized smart replies, I can be a better friend. That's because Gemini can do almost all the work for me. Looking up my notes and drive, scanning past emails for reservations, and finding my itinerary in Google Docs... Gemini matches my typical greetings from past emails, captures my tone, style, and favorite word choices, and then it automatically generates a reply.

Synergized through the agentic power of Gemini, your Google ecosystem can make your sci fi dreams come true. True, we still haven't got our jetpacks, but at least we have the ability to be better friends by letting AI sift through all our correspondence and driving data and write an email for us. Even if you trust them with your stuff, however, keep in mind that every Google Doc you share, every photo of another person you post, every email you exchange is also bringing others, without consent, into your decision to give away your privacy in exchange for "personalized smart replies." And Google is monetizing, directly or indirectly, everything they extract from you—including whatever data they can capture from your unwitting friends.

As discussed earlier, this is why I'm more reluctant to use gmail for sensitive communications than I am my work email. I know many faculty think of gmail as a place to write things to which they don't want their employer having access, but I frankly put a lot more trust in my non-profit employer than I do in the digital edgelords of Silicon Valley. My trust has been eroding steadily for the past 20 years, but it has never been lower than at this current moment, when Google's leadership is joining the train of royal supplicants heading to DC to secure protection from regulation, legislation, and unfavorable anti-trust decisions. Meanwhile, the AI race has only dramatically multiplied the already immense incentives to mine, algorithmize, and monetize everything they know about you—which is pretty much everything if you are using even a handful of their services. And we are all using a handful of their services—if not Google's, then Meta's, or Amazon's, or Microsoft's...

I am picking on Google here because they are in many ways the first pure extraction fiefdom to emerge in the post-Web 2.0 era. But they are far from the only one, of course. Around the time Google was taking down its "Don't Be Evil" motto, Amazon was in the midst of an acquisitions bender that would see them absorb Twitch, Whole Foods, Blink, Ring, and eventually One Medical and even MGM. But it was what they were building quietly on the backend that secured their digital fiefdom more even than Amazon.com itself: AWS.

While retail sales (and increasingly the company's profitable "marketplace" model) bring in the most revenue, by far the most profitable division of Amazon is Amazon Web Services (AWS), which accounts for a full 50% of the company's operating income. An outage in October at AWS revealed for many who had never registered its scale how much of the cloud depended on AWS servers—roughly 30% of the global cloud infrastructure services market. The core retail businesses (amazon.com, Zappos, Audible, Comixology, Whole Foods, etc) operate on notoriously thin margins, while cloud infrastructure services command much higher profit margins. This dynamic—where AWS is a relatively smaller revenue contributor but the dominant profit engine—has been consistent for years and is a crucial aspect of Amazon's overall business model and valuation. Indeed, it is this profit center of AWS that allowed the retail sales business to take on many years of losses in the process of pricing brick-and-mortar retail out of existence. Today, Amazon controls 40% of all online dollars spent—and, most valuable of all as we shift to technofeudalism, all the data regarding who is buying and selling throughout their vast feudal lands—data it can sell to customer and marketplace tenants simultaneously, even as it takes a cut of the sales that generate this data.

Amazon might seem irrelevant to the topic at hand, insofar as they have not moved into the email/messaging/social media markets. But as surely as is Google/Alphabet or Meta/Facebook, Amazon is harvesting every transaction behind the scenes. Unlike in the world of old-timey capitalism, they are not doing all of this to compete against rivals in the marketplace. After all, they literally own the marketplace at this point. No, the goal is to command our attention by servicing our dopamine centers, keeping us enclosed within the fief long enough that we don't notice the rents we pay or care any longer—as we once did—about all the invisible labor we are performing on their behalf and all the data we are handing over with a click of their constantly revised Terms of Service agreements.

I am not putting myself forward as someone who has found a way out of the enclosures of these platforms. I pay my rents—monetary and otherwise—to all of them. I have tried to exit Amazon and Meta territories many times over only to find myself returning, often without even knowing I was once again on their lands. At my university I am required to remain within the secure embrace of Microsoft's cloud, using their Office products and even their terrible Copilot AI, which is built into those same products. I pay my rents to a seemingly growing number of small fiefs, including for software or streaming services. I used to own the software or the DVD's I purchased. Now I pay rent for the privilege of using them, but never owning them.

Where briefly there was the fantasy of the commons of Web 1.0, in which we contribute to the Internet what we can in exchange for what we need, today we are paying rent at every turn, even as we are being strip-mined along the way, transformed into points of data to fuel ever more complex algorithms whose ultimate purpose is to keep us in the enclosure until every penny of rent and point of data has been extracted. At which point we won't be able to afford the monthly rent we pay to our Internet service provider or cellphone provider to be on the Internet in the first place. Exiled from the enclosures, we will be free to be no-people residing in the no-place outside.

So, if I have no route out of this place, nor any admirable model of resistance, why am I opening this survey of digital safety and hygiene strategies with this dystopian overview of the landscape on which we find ourselves? Because while I will focus in what follows largely on dangers that are for the most part digital analogs or avatars for the criminals, bullies, would-be tyrants, and sociopaths humans have been dealing with for centuries, we should never forget that the whole digital realm has been coopted by a new kind of legal theft—one neither exactly capitalism nor exactly feudalism, but something new only now just beginning to come into focus. When we are online we are always on land that no longer belongs to us, using tools we helped build but which we do not own, and under contract to techlords who see us only as resources to be leveraged for the expansion of their domains. Approach everything you do in the digital realm with the understanding that you are not on safe ground. You can develop all the safe strategies below and multiply them a thousandfold, and that essential fact will not change. The safety measures discussed below matter, and they will meaningfully reduce the harm that can come your way within these enclosures. But never let them fool you into believing you they care about you or that this is a safe place on which to build a home—still less an identity.

OK, now on to the more mundane strategies to keep you safer—and to help develop habits of deliberate suspicion anytime you open your laptop or pick up your phone.

Web Browsers and Tracking

Let's cut to the chase. Every commercial website you visit is building a profile of you. In 2026, with faculty under scrutiny as never before, your browsing history is another treasure trove of future public record requests or targeted attacks—and unlike email, most people have no idea what's being tracked.

On Google's Chrome browser, everything you do on the web is being tracked—even in "incognito mode" (which hides your activity from other users of your device, but not from Google or your ISP). I strongly recommend to anyone who will listen (roughly 5 people at last count) that they ditch Chrome for other safer options. Pretty much any other option would be better.

For most people, the best option remains Firefox. With a few tweaks by way of extensions, this is all you need to safely conduct your research and your personal life online. Unlike Google (or, god help us, Microsoft's Edge browser), Firefox is operated by a non-profit organization. As such it has no incentive to exploit your data and every incentive not to.

Out of the box, Firefox is already a big improvement over Chrome. But it needs three free extensions to be truly reliable from a digital hygiene perspective. The essentials are:

- uBlock Origin blocks trackers and ads

- Privacy Badger from the Electronic Frontier Foundation—a long-time digital privacy non-profit—this extension stops sites from tracking you across the web

- Firefox Multi-Account Containers keeps your university work in one container and personal browsing in another, so cookies can't follow you from one to another

Download Firefox and add those three extensions, and you have a very stable and secure browser. While I recommend against adding too many extensions, all of which are potential security risks and drags on performance, I also strongly encourage the addition of one more extension, ClearURLs, which strips tracking parameters from URLs automatically.

Why would you want to do this? The answer might clarify a few of the ways in which the Internet is populated by billions of unseen hitchhikers. Think of it like walking through a beautiful meadow in late summer. Not until you get home do you discover you are covered with burrs and a few ticks.

When we stroll through the meadow of the Internet, we pick up a ton of unasked for hitchhiker weeds, including tracking codes that look something like "?utm_source=facebook&fbclid=ABC123". These codes track where you came from and can identify you across sites. ClearURLs gets rid of these tracking codes from any URL you share on social media or email, so you're not inadvertently sharing tracking identifiers (and passing your burrs and ticks) to your friends. This prevents Facebook, Google, etc. from following your click paths across the web—and across your email and social media posts.

As with email there may be times you need more security than even the above configuration will provide. For those occasions there is Tor Browser. Most will never need this. It is certainly not for everyday browsing, as it is very slow and featureless by design. But when you want to be absolutely, 100% confident in your privacy online, this is as close to an invisibility cloak on the Internet as you are going to find—so long, of course, as you don't use your name or other identifying fingerprints at the sites you visit. You can learn more about Tor and how to use it safely at https://www.torproject.org

Many Mac users depend on Safari, and it is a safe and reliable browser that is built to play seamlessly within the Apple ecosystem. My own confidence in Apple's fabled commitment to privacy diminishes with every gilded bauble Tim Cook bestows on the current administration. But Safari's Intelligent Tracking Prevention (ITP) is the real deal, using on-device machine learning to block cross-site trackers by default, and its online fingerprinting defense makes individual devices much harder to identify.

There has been growing concern about vulnerabilities in Safari's underlying WebKit architecture, which can be targeted by sophisticated attacks. There were nine zero-day vulnerabilities in 2025 alone, the most recent of which was patched just a few weeks ago. When using Safari—or any browser—install every security update as soon as it's released.

While Safari remains safe, its ecosystem is very closed. Several years ago, Apple closed off their browser to third-party extensions unless they are distributed through their App Store. What this means in practical terms is that a many developers of vital extensions have stopped building for Safari, unable or unwilling to jump through the hoops necessary to be approved for distribution in the store. Apple claims all of this is in the interests of security, but it probably goes without saying that I don't buy it.

Apple might seem at first glance an exception to the technofeudalism of today's Silicon Valley. Certainly they have worked hard over the years to sell themselves as the alternative to companies like Google and Microsoft. But their App Store gives the game away. A ruthlessly controlled fiefdom that has been a powerful profit center for almost 20 years, the App Store allows Apple to take a massive cut (up to 30%) off of every sale of software produced by other companies simply for the privilege of distributing it through the only marketplace on which Apple allows it to be distributed. As we know well in 2026, such tariffs are ultimately passed on to the customer in the form of higher prices. Honestly—and I say this as an Apple user of almost forty years—the sooner the mystique of Apple's brand falls apart the better.

A year or so ago, I started using a browser called Orion from Kagi (a paid search company). It is now my Internet ride-or-die, but it is not likely to appeal to everyone (for one thing, it is Mac-only). It is built on Safari's WebKit architecture and yet is able (unlike Safari) to work with most of the extensions available for Firefox and Chrome. It is highly customizable, but also pretty high maintenance for the casual user. Nonetheless, I pause here over Kagi as an example of a new generation of small companies that are building business models around protecting your personal data and privacy rather than monetizing it.

Search

We search dozens or hundreds of times a day. If you are searching on Google, as you very likely are, each of those searches is another datapoint they have collected about you—to sell to others and to sell your own desires back to you in the form of targeted ads. I promise I am largely done beating up on Google, which is no worse than most of its peers and better than some. But when it comes to the Internet, Google's saturation into our everyday operations makes it particularly dangerous.

Fortunately, there are alternatives. The original privacy-first search engine was DuckDuckGo, which remains decent enough. In 2022, researchers found its browser allowed some Microsoft trackers, which makes sense since it relies on Microsoft's Bing for search indexing and ads. The trackers are supposedly gone now, but the dependency on Bing's index remains, and for me that is enough reason to look elsewhere.

A better free option is Brave Search which uses Brave's own independent crawler-based index rather than relying on Google or Bing. It doesn't track users or serve targeted ads, but it does collect anonymous usage metrics to improve results, though it claims this data can't be tied to individual profiles. I have spent time with Brave Search, and it is decent and getting steadily better. But for scholarly research, I do not find it is sufficiently robust to yield useful results on niche searches.

Startpage takes a different approach: delivering Google's search answers while stripping away identifying data before showing you results. It also offers an "Anonymous View" feature that lets you visit result pages without submitting data to those sites. This sounds awesome, and I might be convinced to use it, if it wasn't owned by System1, a U.S.-based advertising company. There is just no conceivable version of 21st-century reality wherein a publicly-traded advertising company is building a privacy-focused search engine with no intention of exploiting it. I hope I am wrong. But I doubt it.

My own search engine of choice—indeed the only one I use—is Kagi. What makes Kagi different is also what makes it hard to swallow for so many: Kagi charges for the use of its search engine. We are so accustomed to the idea of "free" search that people look at me funny when I mention that I pay for the privilege. And yet, of all the rents I pay online, this is the one I feel best about. I am paying for a unique search database that is every bit as good, and increasingly better, than Google. It is definitely faster. In addition, I can count on anonymized user data, no ads, no telemetry or tracking, and customizations galore—including filtering out AI-generated images from results.

Is it worth it? That is entirely up to you. If nothing is free, it is a matter of the currency by which you choose to pay for your services. I will always choose giving money to a company I trust over giving personal data to a company I don't. One way or another we are paying. Since we have already established that I have no moral high ground on which to preach the virtue of my own choices, I say this with no certainty that I am right. There seems to me nothing wrong with deciding that, having already been mined for years for every bit and byte of data, it does't much matter to you if they get a bit more in exchange for free search.

For me, the decision to switch was actually less about the data mining, than about my growing frustration with navigating the search results on Google. The answers were there, but to find them I had to sift through layers of Paid Shopping Ads (with images), Text Ads (marked with tiny "Sponsored" labels), "People Also Ask" boxes—all before I got to what I had asked to find. And this was before Google decided to bake in Gemini overviews, with the goal of keeping me from even clicking on the links to the websites I had searched for. I was starting to feel like I needed a search engine for my search results. My ADD-addled brain did not have the focus to wade through the growing layers of unasked for slop.

AI

I have colleagues who insist they will never use AI, and I do not have the heart to tell them they have been using it for some time now—in the predictive text on their iPhones, the reverse image searches they perform, or the personalized Spotify playlists they listen to. I don't say such things because I try hard not to be that guy, but also because I believe there are very good reasons to want to avoid AI. The fact that it is a regular assistant in my research is something of which I am neither proud nor ashamed. That said, I have found it an increasingly useful partner, to the point where I suspect that more and more faculty will soon find themselves incorporating AI into certain aspects of their work. In many universities, AI is being foisted on faculty, making it still harder to resist.

Weirdly no one is talking much about digital safety and hygiene when it comes to these tools. They should be.

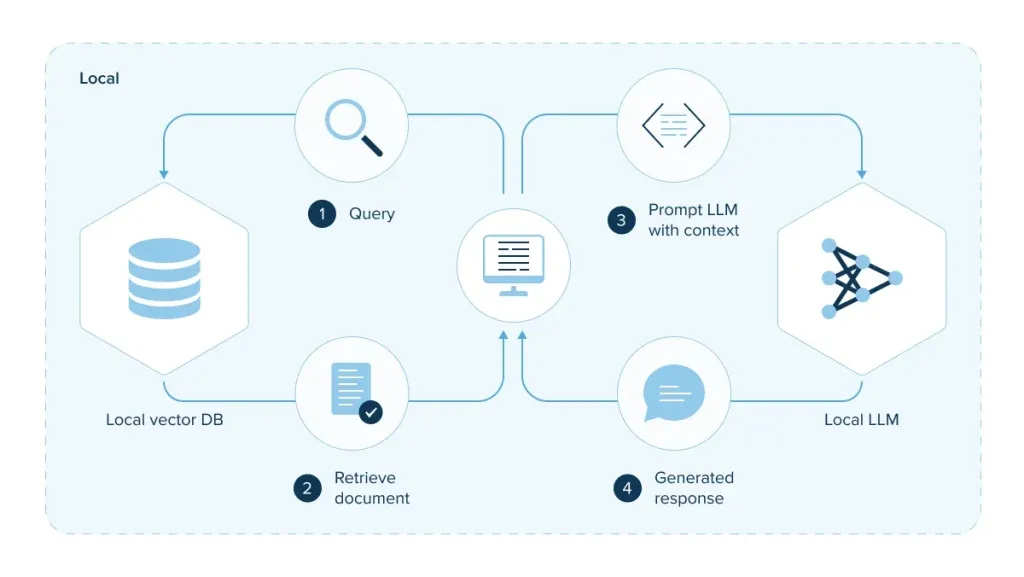

When it comes to AI, there is only one truly safe approach: running an open source LLM locally installed on your own machine. DeepSeek, Qwen, Mistral, and Llama are excellent choices for local LLMs, all coming in different model weights so you can select the model that will run effectively on your consumer machine. Probably the best option for a local model that comes closest to approximating the power of the frontier commercial models is DeepSeek, released in 2025. Most of the frontier models—Claude, ChatGPT, Gemini—have long stopped releasing open source models, locking the data they have stolen from the commons behind proprietary walls (a pattern with which we are by now all too familiar). A local LLM means no telemetry, no logging, no cloud servers—completely offline operation.

Where things get a bit confusing and potentially dicey is that many of these models are also the names for cloud-based LLMs. DeepSeek not run locally is running off servers in China, subject to PRC regulations and government access, with no transparency as to how your data will be used. That is to say, local DeepSeek is my #1 LLM recommendation for secure AI access, while DeepSeek at chat.deepseek.com or via the DeepSeek API is my absolute lowest recommendation.

Most people won't want to run a local LLM and for good reasons. They are slower and less powerful than the frontier models like ChatGPT, for one. In addition, they have a fairly steep learning curve in terms of setting up and tweaking. And unless you have a new and fairly powerful desktop, you will probably be running a very small model locally, which will feel decidedly flyweight compared to what you find at the commercial LLMs.

For that reason, the decision to use LLMs will involve risk, including moral risk. After all, we know that the large data sets which constitute the "knowledge bank" of these tools has been hoovered up from decades of other people's ideas, words, creation, labor found on the Internet along with books, newspapers, and other intellectual property which was absorbed into the models without permission or compensation.

Knowing this, you might well ask, how can I even use these tools to support my own research? The answer would be another long post, which, if there is interest, I would be glad to share at another time. For now, I can say that it was not a decision arrived at lightly, nor is my embrace of LLMs wholesale or without reservations. When Dall-E first came out 4 or 5 years ago, I spent some time trying it out. Following a pattern familiar to many encounters with AI, I was initially dazzled only to find myself feeling increasingly queasy. Leaving aside the theft of individual artists' work to power these AI "creations"—nauseating enough—and even the immense resources image generation requires, the products, then and now, just felt yucky. No matter how slick or responsive to my prompt, there was something about looking at this imitation of creativity that felt like a fundamental violation of what it means to be human. So even before ChatGPT 3.5 was released to the public, I had determined never to use AI to produce anything—art, video, music, prose—that substituted for or presented itself as a creative work.

Anti-AI purists will suggest, no doubt with some justice, that I am slicing my moral compromises very fine indeed. In the end, the thinking over the past three years that has led me, provisionally at least, to this point is based on three questions I ask myself:

- is my request something for which I would or should be paying someone?

- is my request offloading creative or intellectual work to the LLM, which will come at a cognitive cost to me and as an act of theft to those whose already-stolen labor is doing this work for me, unasked and uncredited?

- is my request something that will consume more energy than doing the same work via a series of web searches?

This last one is worth pausing over as an illustration of how I justify, self-servingly or not, the labor I share with AI. The most current estimates suggest that a prompt asking for a text-based response to a query is (very) roughly 10x as much energy use as a standard google search. In order to find that number I made such a query of Claude, asking it for a range of different approaches to the answer and updates on current data and methodology. Knowing well my own working patterns, I am confident that arriving at the results I needed would have taken me at least 10 Google (or in my case Kagi) searches, as I refined my queries and worked to filter out less reliable industry-backed studies from other very different approaches and answers to the question. I also know myself well enough to know there would have been a half-dozen rabbit holes along the way, before I remembered what I was after. For me, at least, using LLMs in this way is focusing, efficient, and, I strongly suspect, often an energy-wash from the ways in which I conducted this kind of research in the past. In comparison, video generation consumes, by one estimate at least, 30× more than image generation and 2,000× more than text generation.

All of these numbers are, of course, silly when we think about them too long. After all, any calculation of energy use depends on which model you are using, how many tokens is the context window, whether you are using a reasoning model, and so on. The cost of generating images has actually come down considerably since 2023, while the cost of deepfake video generation can be astronomical—in terms of both energy use and individual and societal harm. As best I can, I keep these factors in mind, using smaller non-reasoning models for simple queries and turning to traditional search for the most straightforward. I know I would be fooling myself if I don't imagine an additional cost to using AI as a research assistant, just as there was 25 years ago when I started using Google and online databases instead of biking to the library to look up the information I was seeking. I have decided I will be at relative peace with that tradeoff for now.

Setting the moral and ethical hygiene of AI use aside for now, let me return to the more concrete issues of digital security and safety.

If you are not using a local LLM, the next safest bet is also the most useless in terms of any help to you as a researcher. Apple Intelligence, available through Apple devices, performs almost all of its processing on-device, with online compute deleted immediately. But there is no getting around it: Apple is thousands of miles behind in the AI race, and mostly for understandable reasons. Their commitment to privacy and to maintaining as much compute on the device (within their hardware ecosystem) holds them back in competing head-to-head with frontier cloud based models. Of course, they are fine for now with their users choosing to make choices in terms of using any of other models on their devices. In the meantime, they are sitting on mountains of cash they will likely use to buy the AI they want when they find the right solution. As it is now, Apple Intelligence is a souped-up version of Siri, helpful in navigating your personal affairs but not in any way a research assistant.

Which brings us to the cloud-based frontier models. The LLM I used daily, and to which I subscribe, is Anthropic's Claude. I spent a fair amount of time over the last two years speed-dating a range of models, but it was clear to me from early on that Claude was a good fit for the ways I work and think. It used to have a best-in-class privacy policy among the major models, with no training on user data as the default setting. As of September 2025, however, that strong selling point was weakened with a shift to the industry-standard default "opt-out" for training on personal data.

The shift from privacy by default to privacy only if you opt out is disappointing, and it points towards the desperate drive of all of these frontier models for ever more training data in their feverish and absurd pursuit of AGI. Having scraped the Internet and anything else they can find for data and still finding themselves far from the Artificial General Intelligence they crave, they want your interactions with their models for still more training data.

There are plenty of reasons to be skeptical—especially as these absurdly over-leveraged companies are starting to realizing they might never be profitable—that we are not already or very soon will be the product (especially when using the free models). While I am comfortable with Claude for now, I keep a keen eye data privacy policy changes (or better put, on the qualified folks who keep an eye on such things).

I have lost faith in ChatGPT for a range of reasons, and not only because I find Sam Altman to be the least believable person I have ever heard open his mouth. Their recent push towards advertising is especially concerning, as this never bodes well for any Internet platform (see Google, above). But even before ads arrived, ChatGPT was not a good tool for anyone concerned with privacy. By default, ChatGPT uses all your conversations to train its models, and your chat history is saved indefinitely unless you manually delete it. Using temporary chat guarantees your chats will not be used or retained, but for most research use-cases temporary chat is not an effective strategy. I will also say that ChatGPT, which had all the advantages out of the gate in fall of 2023, is simply no longer the best for most scholarly needs. For my use cases, at least, both Claude and Gemini are now more dependable models.

Of course, Gemini brings us back to my old bête noire Google, and there are good reasons to be wary of Gemini as a result of its parent. Even with settings disabled, chats can be sent to human reviewers at any time and are retained up to three years—unless you are using (as I am) an instance through Google's education license. And as we saw earlier, part of how Google sells Gemini to the consumer market is through its deep integration with other Google accounts and services.

Frankly, I would not be using Gemini did I not have secure access through my university. As a result of this contract, my engagement with Gemini is locked down within the university and does not travel back to Google—nor is it reviewable by humans. It allows me to work with more sensitive documents I would never want to share with LLMs outside of the university's security protections.

Many in higher ed have or soon will have similar arrangements contracted by their institutions with one of the frontier models. They are a good thing in that they provide meaningful protections of secured and private data in terms of potential misuse by the AI company. At OSU we currently have access to Gemini and Microsoft's Copilot (the latter is so bad I try and forget it exists). Google for Education's contracts with universities like mine ensures that our LLM use is covered by a Data Protection Addendum (DPA) and that our data is never used to train AI models.

That said, I am fairly certain that many universities, including my own, are overselling the trustworthiness of these AI partners. Both Copilot and Gemini in the university setting advertise that they "support compliance," not that they themselves comply. This is lawyer-talk for "we provide the technical infrastructure that can allow compliance, and the actual compliance is up to the university." The university, inevitably, passes that same compliance responsibility on to us.

When I attended a splashy event celebrating Google's new partnership with OSU, the Google reps proudly displayed FERPA and HIPPA badges on their slide decks. Indeed, my university's published guidance is that we can use our university password protected google accounts—including NotebookLM and Gemini—"are approved for use with Research Data, Research Health Information, and FERPA data" (not, quite rightly, with HIPPA data). Google has good reason to take these security commitments to education institutions seriously and I do believe–despite my general feelings about the company—that they can be trusted so long as one stays within the university's password protected environment. For me, anything I do involving sensitive data, university business, or the like goes with my university's instance of Gemini. Nonetheless, I think long and hard before I put anything sensitive through AI of any kind, especially student and institutional data.

Google is competing hard with Microsoft in the higher education sector and they have, so long as the contest is being waged, every incentive to be aggressive in their privacy commitments to these clients. And of course universities like OSU have themselves made big public commitments to "AI fluency" initiatives, meaning they too have a strong incentive to present these tools as "safe." It would be a jarring disconnect if the university announced that every student and faculty member is going to have access to enterprise AI tools, only to let them know that it is not safe enough for FERPA data.

What gives me some pause is that other universities without massive "AI initiatives" are being more cautious in their guidance—despite having the same contracts. My university's energetic AI initiative is almost certainly driving a more generous interpretation of the Google DPA. They've made such enormous public and financial commitments that they need do everything on their end to make the initiative viable. Other universities without such commitments can afford to be more conservative. For example, Boise State doesn't have a massive AI initiative to protect, so they can afford to say "don't use FERPA data" without risking being called out for mixed messages.

For now I am taking both Gemini and my university at their word. But it is a reminder that institutional priorities can shape data privacy policies. The technology and contracts are the same, but the risk calculations are completely different based on what the university has committed to publicly in the AI space. In the end it will be individual faculty who are responsible should the guidance prove overly optimistic—and in the case of student data, it will be the students who are exposed. Proceed with care, as in all things digital—especially when student data is involved.

Social Media

This one is easy. I doubt there is anyone who does not know with certainty that everything they do on social media is forever. And public. This is true regardless of the social media platform or whether the post is public or private. It matters not at all whether the forum to which you post is populated entirely by people you would trust with your most outrageous joke and inflammatory take.

For those of us working at universities—students, staff, faculty, and administators—social media is a hunting ground for people wishing to curry favor and/or inflict damage on higher education. The reasons social media posts are so valuable are clear. They provide the "evidence" to backfill the absurd and baseless narratives which have authorized the ongoing assault on higher education. Calling professors "the enemy," as the Vice President did, doesn't require evidence to back up the charge. But how delightful when "evidence," however out of context and anecdotal, can be circulated via screenshots and amplified through the outrage machines that have fueled this administration's rise to power.

Obviously the safest strategy is to have little to no social media presence. I remain on social media, but I am definitely more cautious than I once was (I am also many years sober now, which certainly helps). I am also protected, at least in part, by the privileges of tenure—privileges available to fewer of my colleagues with each passing year. Too many faculty without such protections (and some with them) have lost their jobs because of social media posts that should have been, in any normal time, protected speech—especially for those working at public institutions.

If there was any doubt about the intensity of the spotlight on faculty social media accounts, the wave of investigations and firings following the murder of Charlie Kirk surely erased it. At least a dozen faculty nationwide faced termination or discipline in the two weeks following Kirk's death, with conservative online influencers and politicians sharing screenshots to amplify pressure. One tenured professor at Austin Peay State University was fired, later reinstated following a successful lawsuit. But many without tenure were fired or suspended only to see their contracts unrenewed.

This has been a growing pattern for some time, first gaining visibility with the case of Steven Salaita in 2014. In 2024, Maura Finkelstein became the first tenured professor to be fired for social media posts critical of the state of Israel. Her nightmare began with an anonymous alumni petition demanding her firing for an Instagram post, accompanied by thousands of bot-generated emails sent to administrators. Her dean then shared her post with the campus Hillel director who sought out a student to file a formal complaint, despite the student having never taken a class with the professor. Armed with the student complaint and fueled by the social media storm, she was fired for violating the anti-discrimination policy. AAUP would censure the college, but it is clear that in this day and age the reputational harm generated by ginned-up social media outrage trumps any concerns about violating norms that have governed higher education for the better part of a century.

Because Professor Finkelstein was employed at Muhlenberg College, a private institution, she was not protected from state impositions on free expression outside of her professional speech. But the case of Kate Polak at Florida Atlantic University demonstrates how faculty at public institutions can no longer count on the first amendment to protect them from such concerted attacks.

Along with two other FAU faculty members, Prof. Polak was suspended for social media posts on Threads and Facebook in the wake of Kirk's murder. FAU hired Alan Lawson, a former conservative Florida Supreme Court justice, to investigate, an investigation that went far beyond the specific posts—including a review of Polak's private Facebook page and questions about a protest she attended.

In the end, the two tenured FAU professors were reinstated, suggesting that tenure still serves to restrain the desire of red state public universities to throw their faculty to the mercy of grandstanding legislators and the Internet mob. I don't suspect that to remain the case for much longer. But Kate Polak, like the majority of faculty in the 2020s, was not protected by tenure, despite being an accomplished scholar and teacher. She too was ultimately cleared of wrongdoing, only to learn that her contract would not be renewed at the end of the academic year.

The FAU playbook is playing out across the country, chilling the speech of the majority of faculty work without the safeguards of tenure:

- Ginned-up outrage targeting a faculty member's social media post

- State legislator and/or trustee demanding the faculty member's termination

- Administrative leave pending an investigation

- The hiring of a "credible" conservative investigator

- An investigation the widens beyond the supposed offense in search of more "evidence" to turn against the faculty member should they choose to fight back in the courts

- The investigation drags for months while the media storm cools

- If it is a public institution and the professor has tenure, quietly reinstate them and hope no one notices

- If they don't have tenure, claim "operational interests" for not renewing their contract

All of this of course demonstrates that faculty are more vulnerable than ever, and most vulnerable when and where they feel themselves safest: expressing their individual opinion on their social media platform of choice.

The practical advice is likely obvious, but worth spelling out:

- Delete old posts regularly, and clean up your history to ensure that you would be comfortable with your administrators, trustees, and legislators reading what is posted.

- Add language in your social media bio stating that opinions are your own and that you are speaking as a private individual and not as an employee of your institution

- Think twice before posting, and check in on your previous night's posts the next day to see if they still pass the Chronicle test

- Avoid posting about institutional politics

- Always assume private groups are not private and that screenshots will leak

- Your social media friend group is not your only audience when you are on social media.

- 90% of your social media "friends" are not actually real friends and could turn on you in the blink of an eye

I am not going to recommend any social media platform as safer or more secure, as doing so would give false promises. Those that are not fueled by algorithms working to generate outraged engagement are safer precisely because they are less effective as social media. Certainly for mental health, an algorithm-free platform like Mastodon or Bluesky will bring you less pain because it will bring you less engagement. But these platforms also remind us that as much as we complain about the algorithms which have programmed us to turn ourselves into brands ready to do battle in the marketplace of outrage and injury-collecting, it is those algorithms and the dopamine itches they scratch that made social media so addictive in the first place.

Many younger academics today assume social media is necessary to promote scholarship and network. They are not entirely wrong; as travel budgets decrease or disappear, social media often seems like the only way to network with others in the field. But if this is what keeps you from leaving social media, approach it as you would engage at a scholarly conference. At an in-person conference, you assume that anyone you meet could well be on the hiring committee for the job you are applying for or reading your manuscript when you submit it to the publisher. Social media for academics is much the same, with the added reality of knowing that there are people lurking in the shadows waiting for you to say something they can use against you or your university.

Look to other means of communication to talk politics or complain about your dean or trustees. Although the 21st century has worked to convince us otherwise, our social media selves have never been our true selves. We know this because in our real lives we are fully capable of engaging meaningfully with ideas which might require, for instance, changing our mind or holding two seemingly incompatible ideas simultaneously. Heck, we are likely especially good at this, since we do complicated ideas for a living. And yet so many brilliant faculty I know—people who can find shades of gray in even the most seemingly black-and-white proposition—become rigid and doctrinaire when engaging with challenging ideas on social media. The wise ones walk away. The rest of us remain for ever-decreasing returns, wondering why our popular posts ultimately depress us more than the ones that are ignored entirely.

In Doppelganger Naomi Klein describes the ways in which social media ends up ossifying us into fixed brands. "Brands are not built to contain our multitudes," she writes, "they demand fixedness, stasis, one singular self per person":

The form of doubling that branding demands of us is antithetical to the healthy form of doubling (or tripling, or quadrupling) that is thinking and adapting to changing circumstances. That would be a problem at any time in history, but in a moment like ours, with so many collective crises demanding our deliberation, debate, and elasticity, the stakes feel civilizational. (66)

If our selves are not ourselves on social media but manically curated brands weeded of anything that might sully its distinctive easily-recognizable lines, the vast majority of our "friends" in these spaces are not in fact friends—at least not in those spaces. I was reminded of this the other day when scrolling through one social media platform and found one "friend" proclaiming that he will "unfriend and block" anyone who posts an AI avatar of himself while another dared anyone in his "friend" group to contradict him on the meaning of zionism. Both of these people are and remain actual friends in real life, and in the actual world they would never lay down such Manichaen ultimatums. In the real world if I wanted to make the case for an AI avatar (I don't) or for a more nuanced understanding of the range of meanings American Jews might attach to the word "zionism" they would both engage and listen. They would no doubt disagree, perhaps strongly, but they would not "block" me. Or maybe, because we have all lived so much of our lives in these spaces, they would, feeling more loyalty to the absolutes of their brand than the messy ambivalence of being actual humans in a terrifyingly unstable world.

The tripling and quadrupling that we must allow our thinking freedom to engage in at this moment of global and national crisis cannot be accommodated to social media. Maybe it is time to look elsewhere for the real community we need now more than ever (he says as he prepares to share this absurdly long and deeply ambivalent post on social media).

VPNs

I have struggled to explain to folks what a VPN (Virtual Private Network) is and why it is something that should be always at hand when they take their digital life on the road. I asked Claude for a good way to explain it, and it suggested thinking of a VPN "like putting your internet connection in an envelope before it leaves your device." I like that metaphor, but it brought to mind a more vivid analogy. Think of the VPN as an internet condom that should always be used when engaging with networks and sites that seem potentially... sketchy.

What is a sketchy network or site? First and foremost, any public wifi network (on campus, at a hotel, the airport, the mall). If no password is required it means there is no security whatsoever. The providers of these public wifi connections rarely mean harm. Starbucks wants you to make visiting their shop a daily habit, and providing free wifi has proven a powerful lure. Your hotel is competing with other chains offering free wifi. The airport is serving a stressed out public trying to navigate their travel and connections.

But with no security protocols in the network, anyone can camp out—at the table next to you or the hotel room below you—and use a program such as Wireshark to capture all the data flowing across that public wifi network. Wireshark is a totally legal tool for network administrators. But no one is administering a public network, so in this context such a tool can be used to see:

- Every website you visit (if not using https)

- Login credentials sent over unencrypted connections

- Session cookies—the digital keys that keep you logged into websites

- What you're searching for

- What cloud documents you're accessing

You may think you are safe if you don't visit any websites that are not https. But sadly on a public network, you are not, and in these cases https often serves to create more carelessness with online behavior when on public networks. Many websites you visit send a session cookie to your browser that says "this person is logged in, don't make them type a password again." When that cookie travels over public unencrypted wifi, the digital pickpocket in the crowd can capture your session cookie, copy it into their browser, and effectively become you on that website—without ever knowing your password. The same can happen with email (there is a reason ransomware and other attacks often happen to folks shortly after they travel).

It can get worse. If you are not sufficiently scared by the above scenarios to install a VPN and use it every time you are on a network you don't know and trust (which is any network that anyone can access without a password), here's one more scenario. You are sitting in a coffee shop and go to log into their public wifi. You see two networks with similar names to the name of the coffee shop and log in to one. Turns out one of those public wifis belonged to the coffee shop, but not the one you chose. That one is a spoof network connecting you to the pickpocket's laptop running nearby. You can use the Internet through their connection and aside from noticing the connection is kind of slow you won't notice anything amiss. Meanwhile, the "owner" of the network you just connected to is seeing everything you do, even your visits to https sites. They have access to email credentials, university login tokens, unencrypted research data, and quite likely something potentially compromising of a personal nature that they will find when they use those credentials later.

Hopefully, you are scared straight if you were not already practicing safe public wifi and will never engage without your VPN turned on before you connect to an unencrypted network. With a VPN, the pickpocket can't see anything you do and cannot hijack your session.

99% of the time you do not need to use a VPN on your home network (so long as you have the network set up with solid security protocols) or with your password-protected network on campus. Frankly you don't want to use a VPN when you don't need to, as it will slow down your work considerably as the VPN bounces your connections across their relays. But if you are engaged in research requiring you to visit sites at which you would rather not leave behind your IP address, a VPN is in order.

A concrete example: I am trying to summon the resolve to research the phenomenon of white nationalist speculative fiction, a genre which has proved remarkably influential in the generational transmission of hate. To learn enough about this topic, I will need to delve into some of the most loathsome corners of the Internet, places I definitely do not want to be leaving breadcrumbs. A VPN allows me to conduct this unsavory research without leaving a record of my visit that could be traced back to my ISP or to my university.

VPNs are much more affordable and easier to use than they once were. I personally use ProtonVPN, which runs about $5/month a la carte. There is a free tier for one device to try it out, but you will want it for any tablet, phone, and laptop you move around with, and the paid tier will cover them all. ProtonVPN is Switzerland-based and uses open source code, and unlike some rivals such as NordVPN it does not use Google Analytics. Aside from Proton, do not use any free VPNs (if it's free, you're the product—which when it comes to a VPN is the last thing you want).

There are other good choices at comparable prices including Surfshark, Private Internet Access (PIA), ExpressVPN, and Mullvad. You can trust recommendations from respected tech sites such as CNET and techradar and focus on the best deal among these and quite a few others. But do not leave home without a VPN in your back pocket.

Phew. Time to move on from what I promise will be the longest post I will ever share. If you read through some of this, I hope you found something useful as you figure out your own choices of armor before entering these haunted grounds. If I got something wrong or if you have other suggestions or recommendations, please let me know. This is definitely one area where I can never afford to stop learning.

Subscribe (always free)

Subscribe (free!) to receive the latest updates

Member discussion